The Japanese and the Fox — A Bridge Between Worlds Seen and Unseen

For the Japanese, the fox has long been regarded as a singular presence.

A faint sense of something watching on a dark country road.

The sudden feeling of a gaze upon one’s back deep in the mountains.

Even when no form can be seen, there are moments when people sense that “something” is there – and very often, the figure imagined at the edge of that awareness is the fox.

A white fox standing quietly beyond the vermilion gates of a shrine.

In old tales, a fox that takes on human form, at times misleading people, at times guiding them.

Sacred and yet slightly unsettling, familiar and yet never entirely safe – the fox has come to embody this inner tension in the Japanese imagination.

Why, then, have the Japanese long felt such a particular affinity and unease toward the fox?

And why does the fox continue to be regarded as a sacred presence even today?

Tracing the fox through faith, language, and landscape leads us deep into the spiritual undercurrents of Japan.

The Origins of the Fox and Inari Worship

A Deity Who Sustains Everyday Life

Any discussion of the Japanese and the fox must begin with Inari worship.

This tradition is often traced back to the Nara period (8th century CE), to Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto.

There, the deity Inari – originally a mountain god associated above all with rice and the five grains – came to be revered as a guardian of harvests and daily sustenance.

In an agrarian society, rice quite literally meant life.

People entrusted their hopes for a good harvest to the deities of the mountains and the fields, and offered prayers in gratitude for each year’s yield.

Over time, Inari came to be worshipped not only by farmers, but also by merchants, artisans, warriors and townspeople.

The deity’s role expanded from “god of the harvest” to a protector of livelihood more broadly – a guardian of food, clothing, and shelter woven into the fabric of ordinary life.

Divine Messengers – The Role of the Fox at Inari Shrines

Why, then, do so many Inari shrines have foxes rather than the lion-dog guardian statues (komainu) seen at other Shinto shrines?

The reason lies in the belief that foxes serve as Inari’s messengers – shinshi, “envoys of the deity.”

Foxes appear and disappear at the margins of cultivated land, slipping through fields and edges of woodland.

Their elusive movements and sudden appearances impressed ancient observers with an air of mystery.

Living on the boundary between field and forest, village and mountain, the fox came to be seen as a creature that moves between worlds – well suited to bear the will of the deity from the invisible realm into human life.

Thus, at Inari shrines, stone foxes stand where guardian dogs would usually be found.

The objects they hold in their mouths – ears of rice, keys, scrolls and the like – symbolize harvest, treasure, and hidden knowledge.

While komainu are primarily protectors who ward off harmful forces, the fox at Inari shrines plays another role: a figure who conveys the god’s presence, linking the sacred and the human realms.

While komainu guard against outside threats, foxes serve as messengers of the gods.

In this way, the fox has been placed precisely at the threshold between the divine and the everyday.

Mountains and the Sacred Landscape

Inari worship also has a deep connection to mountain faith.

Behind the main buildings of Fushimi Inari rises Inariyama, a wooded hill treated not merely as a backdrop, but as sacred ground itself.

There, the entire mountain is considered part of the shrine precinct.

Shrines, stone markers, and small altars are scattered along its paths, and worshippers make their way from one to another as they circle the mountain, ascending and descending in an act of pilgrimage.

In this sense, Inari is not only a deity of the fields, but also a presence dwelling in the mountain as a whole.

The mountain, set apart from daily life, is a realm governed by a different order than the human village below – a place approached with awe and restraint.

The fox, which appears both near the fields and on the slopes, naturally came to be seen as an intermediary between the god of the mountain and the world of human habitation: a living sign that something beyond the human order is close at hand.

※For more on Japan’s mountain worship, see the separate article.:Mountain Worship in Japan – Deities Dwelling in the Mountains

A Faith That Spreads Across the Archipelago

From these beginnings, Inari worship spread widely.

Today there are said to be around thirty thousand Inari shrines throughout Japan, and at many of them one finds fox statues standing quietly beside the deity’s dwelling.

The rows of vermilion torii gates associated with Inari shrines are equally symbolic.

Passing beneath a succession of gates, one feels gently ushered out of everyday space and into a different layer of the world.

Many of these torii have been donated by individuals or businesses in gratitude for prayers fulfilled or in hope of future blessings.

The names carved into each pillar mark the countless wishes that have been entrusted to Inari over the centuries.

Seen together, the fox statues and the vermilion gates give visible form to a faith that has taken root not as an abstract doctrine, but as a lived relationship between people and the unseen.

The thousand torii gates at Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto.

Traces of the Fox in the Japanese Language

The Japanese language itself preserves many traces of how foxes have been perceived – as beings that appear at the edges of ordinary reality, where boundaries blur.

As long as these words remain in use, the fox’s presence continues to quietly inhabit everyday speech.

“The Fox’s Wedding” – When Sunlight and Rain Cross Paths

The phrase “kitsune no yomeiri,” literally “a fox’s wedding,” is a poetic expression for a sunshower – a moment when the sky is bright and yet rain falls.

The light remains, and yet raindrops descend.

That contradiction, both clear and unsettled, feels somehow out of step with the usual order of things.

In Japan, the strange phenomenon of rain falling on a sunny day is called a “fox’s wedding.”

There are various explanations for the phrase, but one often repeated story is this:

In earlier times, bridal processions moved in long, formal lines.

People imagined that foxes, too, held their own mysterious wedding processions, and that rain was called down to hide these otherworldly parades from human eyes.

In this way, an unusual natural phenomenon was interpreted as a brief overlap between worlds, with the fox as its invisible host.

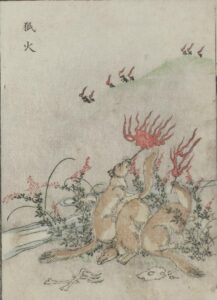

“Fox Fire” – Lights Without a Clear Source

Strange lights sometimes flicker at night in fields, along riverbanks, or at the edges of woods.

In Japan, such wandering lights have been called “kitsune-bi” – fox fire.

Approach them, and they seem to recede.

Chase them, and they slip away.

They are undeniably seen, and yet their source remains undefined.

Before such inexplicable lights, people imagined the fox at work: a creature whose actions belong to a realm beyond straightforward human understanding.

Kitsune-bi, fox fire

Image courtesy of International Research Center for Japanese Studies

“To Be Pinched by a Fox” – When Reality Refuses to Make Sense

The idiom “kitsune ni tsumareru,” “to be pinched by a fox,” is used when something so unexpected happens that one is left at a loss.

The event is real enough, and yet no explanation comes to mind.

One stands there, unable to grasp what has just occurred.

This sense of bewilderment – of being confronted with something that feels true and unreal at the same time – is expressed as “having been tricked by a fox.”

Here again, the fox is the name given to a disturbing gap between experience and comprehension.

“Fox Possession” – When Disturbance Comes From Within

Foxes appear not only in folktales that speak of deception, but also in the older notion of “kitsune-tsuki,” fox possession.

When someone suffered from prolonged mental or physical disturbance with no clear cause, it was sometimes understood as the work of a fox that had attached itself to the person.

The verb “tsuku,” to “possess” or “cling to,” evokes something unseen that draws close and settles inside a human being.

“Fox possession” thus reflects an image of the fox not only as a trickster outside the self, but also as a force that can cross into the inner landscape of a person.

These expressions – “fox’s wedding,” “fox fire,” “to be pinched by a fox,” “fox possession” – all suggest that the fox has been a symbol for those moments when the world fails to align neatly with human expectations.

As long as such phrases remain alive in the language, the fox continues to inhabit Japanese thought as a guidepost marking where the visible ends and the invisible begins.

A Bridge Between the Seen and the Unseen

In Japan, there has long been a way of thinking expressed in the phrase “yaoyorozu no kami” – “eight million gods,” a poetic way of saying that divinity may dwell in countless forms.

※For more on yaoyorozu no kami, see the separate article.:What Are the “Eight Million Gods” That Reside in Japan?

Forests and mountains, rivers and winds, fire, the ripening of rice – all these have been regarded as bearing a sacred quality.

Standing before nature, people become aware of vast forces that exceed human control.

Confronted with that immensity, the Japanese have traditionally responded not only with fear, but also with reverence and a willingness to live in relation to what cannot be fully grasped.

The fox stands precisely where that attitude takes shape most vividly.

In Inari worship, it is honored as the messenger of a deity who sustains daily life.

In the shrine precincts, it sits beside the sanctuary, marking the boundary where the human and the sacred meet.

In language, it appears in expressions like “fox’s wedding” and “fox fire,” giving a name to the strange, the beautiful, and the inexplicable.

Rather than rejecting uncertainty, Japanese culture has often chosen to live with it – to acknowledge what cannot be measured or neatly explained, and to give it a place in story, ritual, and landscape.

The fox is a symbol of that stance: a figure that moves between fields and mountains, between worship and folklore, between the seen and the unseen.

To follow the fox through Japanese belief and language is to approach a way of being in the world that accepts mystery not as an error to be corrected, but as something to be met with respect.

コメント