The Wave That Shook the World — The Journey of Katsushika Hokusai

The Edo-period artist Katsushika Hokusai.

At the sound of his name, most people picture a single moment: a colossal wave about to swallow small boats whole.

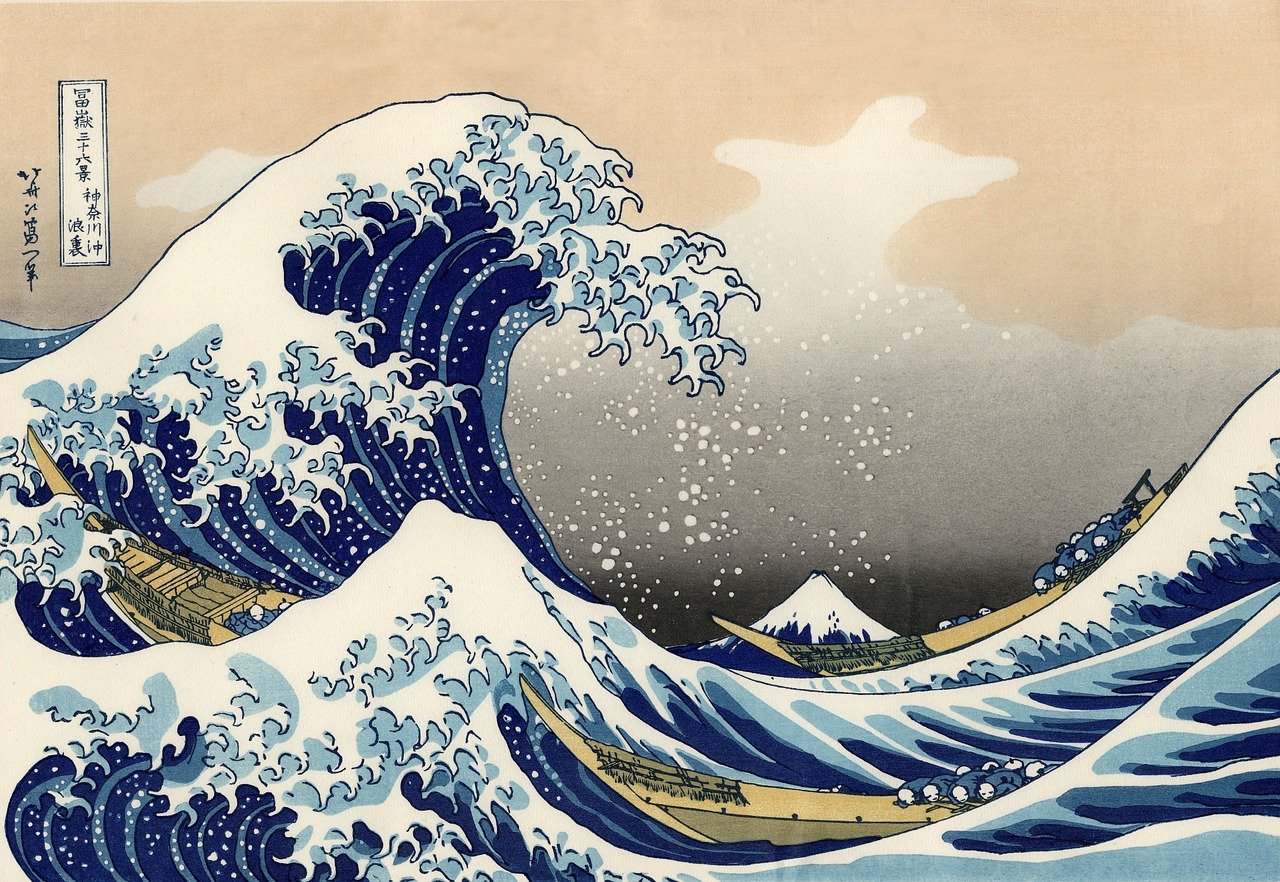

Among the prints of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, none is more famous than The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

That towering wave has come to symbolize Japanese art itself and, at the same time, once startled the world of Western painting.

Yet Hokusai was never a man of one picture.

He held his brush throughout a lifetime, leaving behind an estimated thirty thousand works.

Nearly ninety when he died, he never stopped searching for new ways to express himself—a life story of someone who refused convention and kept reaching for the heights of art.

An Endless Pursuit

Hokusai was born in 1760 in Edo’s Honjo district.

Over the years he moved more than ninety times and adopted over thirty different names.

This was less whim than proof of his restless drive to reinvent his style.

In his final years he called himself Gakyō Rōjin Manji—“the old man mad about painting”—and kept drawing until the very end.

Statue of Katsushika Hokusai at Seikyo-ji Temple

He is said to have remarked, “At the age of one hundred and ten I will truly master the art of painting,” a line that reveals a resolve to climb higher even at life’s close.

Motion and Stillness—Wave and Fuji

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, from the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji

Of all the Thirty-Six Views, The Great Wave off Kanagawa stands apart.

Its sweeping surf curves like a living creature, ready to crash at any moment.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art describes the wave itself as “almost alive.”

Beneath it, fishermen grip their oars, struggling forward despite nature’s overwhelming force.

They are tiny against the sea, yet they do not flee—a symbol, many scholars say, of humanity’s will to endure.

Far in the background, Mount Fuji rises calm and unmoved, lending quiet balance to the scene.

The extreme motion of the wave and the absolute stillness of the mountain share a single frame, and this coexistence gives the picture its striking tension.

A Boundless Eye

Hokusai’s reputation often centers on Mount Fuji, yet his interests reached far beyond it.

Flowers and birds, everyday plants, the bustling streets of Edo, even gods and ghosts—everything became his subject.

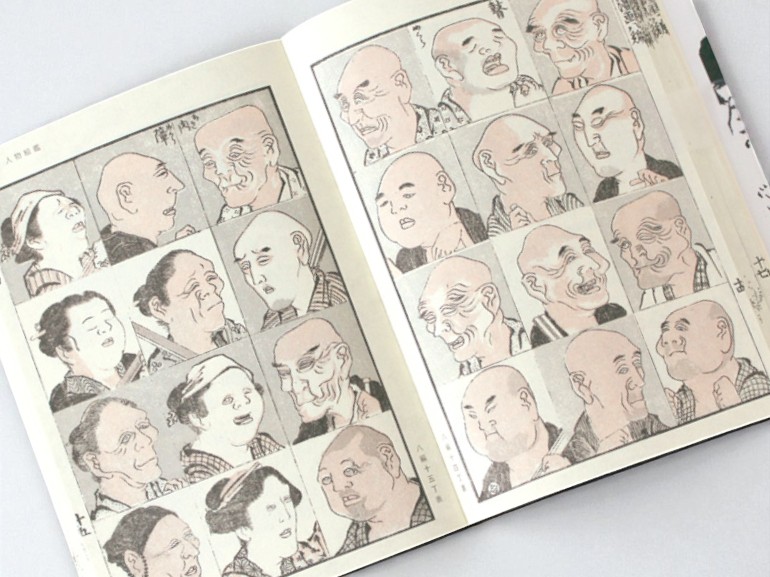

Especially famous is Hokusai Manga, a vast sketchbook capturing gestures of people, movements of animals, tools, and landscapes.

It served as a popular manual in his day and still astonishes with its keen observation and inventive spirit.

To Hokusai the world was an inexhaustible storehouse of motifs.

He filled books, hand-painted scrolls, and single-sheet prints with such energy it seemed nothing lay beyond the reach of his brush.

Hokusai Manga, an illustrated collection by Katsushika Hokusai

Shockwaves Across the Sea

In the nineteenth century Japanese woodblock prints crossed the oceans, sending a jolt through European art and spreading Hokusai’s name abroad.

Exports during the late Edo and early Meiji periods reached international expositions such as the Paris World’s Fair, sparking the craze known as Japonisme.

Impressionist painters were enthralled.

Van Gogh copied Hokusai’s prints, while Monet and Degas absorbed his daring compositions and rhythmic colors.

It is no exaggeration to say that Hokusai stood behind key innovations of modern Western painting.

Hokusai in Everyday Life

Today his work is not confined to museums; it lives in daily life.

Japan’s redesigned 1,000-yen note of 2024 carries The Great Wave off Kanagawa, and since 2020 the nation’s passports feature different scenes from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji on each page.

Hokusai’s works have also been used as designs on Japanese banknotes.

In Tokyo’s Sumida ward, where Hokusai once lived, “Hokusai Street” runs through the neighborhood, its sidewalks and signs decorated with his designs.

Hokusai has long since ceased to be just a celebrated artist; he has become part of Japan’s landscape and its everyday rhythm.

The Unending Wave

The wave Hokusai painted continues to move us two centuries later.

It is more than a single famous print; it is an unending question about the forces hidden beyond what we see.

His works, still present in daily life, speak quietly of nature’s power, human resilience, and an unquenchable drive to create.

Standing before that wave, we too may feel the urge to set out on our own sea of endless exploration.

コメント