In Western countries, Christmas is the undisputed king of the holiday season. Streets sparkle with dazzling lights, families gather around Christmas trees, and the air is filled with the aroma of roasted turkey. It’s like stepping into a heartwarming holiday movie.

Meanwhile, in Japan, Christmas gets a respectful nod—but it’s New Year’s Eve that truly takes center stage. For the Japanese, December 31st is more than just the last day of the calendar; it’s the ultimate “year-end audit” of life. While the West puts its energy into twinkling trees and gift exchanges, Japan pours its heart into cleaning and soba noodles. Why the difference? It all comes down to Japan’s unique culture, where welcoming the new year with a clean slate (literally and figuratively) is paramount.

New Year’s Eve in Japan kicks off with a bang—of cleaning supplies hitting the floor. “Osoji,” or the big year-end cleaning, is an all-hands-on-deck operation. Families scrub every corner of the house, sweeping away a year’s worth of dust, clutter, and bad vibes. The soundtrack to this domestic warfare? Festive TV music programs, of course.

But cleaning isn’t all hard labor. It often turns into an impromptu stroll down memory lane. One moment you’re dusting a shelf; the next, you’re flipping through old photo albums and reminiscing about that time Uncle Ken wore a Santa suit to a summer barbecue. Osoji may start as a chore, but it usually ends with laughter and nostalgia—making it a peculiar but cherished New Year’s Eve ritual.

Once the house sparkles, it’s time to tackle the next mission: shopping. Supermarkets and department stores transform into battlegrounds as families race to gather ingredients for osechi, Japan’s traditional New Year’s feast, and ingredients for toshikoshi soba, the essential year-crossing noodles.

Modern times have ushered in a new trend: ordering osechi from department stores or online. These professionally crafted feasts are not only gorgeous but also a lifesaver for busy families. Yet, the DIY spirit persists. In many kitchens, parents and grandparents lovingly prepare simmered vegetables, golden egg rolls, and sweet black beans. The kitchen becomes a hive of activity, with everyone lending a hand and sharing the sentiment, “This is the final big task of the year.”

As evening falls, families gather around the TV for one of Japan’s most beloved traditions: the “Kohaku Uta Gassen” (Red and White Song Battle). It’s a medley of the year’s top music hits, featuring performances from iconic singers to rising stars. Everyone has a favorite performer to cheer for, and playful debates about which side deserves to win fill the room.

Of course, not everyone is glued to the TV these days. Some families opt for Netflix marathons or intense gaming sessions. Still, the sight of loved ones munching on hotpot or snacks around a screen remains a classic way to end the year.

As midnight nears, someone in the family quietly slips away to start boiling soba noodles. There’s an unspoken rule in Japan: you can’t cross into the new year without slurping a bowl of soba. As steam rises from the bowls, family members share heartfelt reflections, saying, “It’s been quite a year, hasn’t it?”

At the stroke of midnight, temples across Japan begin ringing the “joya no kane” (New Year’s Eve bells) 108 times. Why 108? According to Buddhist teachings, humans have 108 earthly desires, and each chime is said to cleanse one of these attachments. It’s a solemn and peaceful way to mark the transition into the new year. Even the rowdiest kids quiet down to listen, and the sound of the bells stirs a quiet resolution: “Next year, I’ll be better.”

New Year’s in Japan Begins with Hatsumode

When the new year begins, many Japanese people start preparing for “Hatsumode,” the first shrine or temple visit of the year. This traditional event includes “Ganjou-mairi,” where people visit shrines early in the morning. The sight of families and friends walking along the cold, quiet night streets, still enveloped in the calm of the night, is truly unique to Japan.

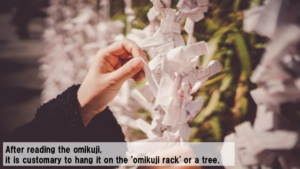

Upon reaching the shrine, visitors will find a long line of people waiting to pray. The light conversations exchanged while waiting and the excitement of welcoming the new year help to forget the cold. After the prayer, it’s customary to draw an “omikuji” (fortune slip) to predict one’s luck for the year. Additionally, purchasing a new “omamori” (amulet) and returning the previous year’s one is a traditional practice at Hatsumode. Many foreigners are surprised by this custom, but in Japan, it’s common to replace the omamori every year.

And of course, the final delight is the warm “amazake” (sweet rice drink) or “oshiruko” (sweet red bean soup). That one cup, which gently wraps around your frozen body, carries a special sense of happiness. Hatsumode is a time to embrace the hopes of the new year, with a bit of excitement as you take your first step toward the future. The experience at the shrine, from beginning to end, adds a special moment that symbolizes the start of Japan’s new year.

New Year’s Eve in Japan is a day of reflection, renewal, and quiet joy. From sweeping floors to slurping noodles, from the chime of bells to the warmth of a shrine visit, every ritual carries a sense of purpose and gratitude.

So, if you’re ever in Japan on December 31st, grab a mop, a bowl of soba, and a spirit of adventure. Because in this corner of the world, the way you say goodbye to the old year sets the tone for the new one.

コメント